There is a delicate balance between writing for pleasure and writing to be read. Something happened to me when I was 17 that upset my understanding of these two separate practices. This was thanks to a nosy friend of mine, who confessed rather shamelessly to snooping through my writing.

“It was the only way to find out what’s going on in your head,” says Lucy. Her face is red and prickled and she looks like a small forest animal defending itself against a farmer’s boot. “You should have hidden them better.”

I tell her I hid my diaries as well as I could, in the back of my closet on a shelf, with an old sweater on top of them, and that she shouldn’t have looked so hard.

I burn with anger, thinking of how I willingly gave her the key to my house while my family was traveling, completely oblivious to the impending act of intrusion.

It was dark, and she was disappearing down a lamplit street, having walked out of a birthday party early after picking a fight with another guest. I felt bad for her and I was leaving for Paris the next day, so I squeezed out of the house and down the lane to tap her on the shoulder. I offered her the key and thanked her for agreeing to look after my cats.

And I went home that night and hid my diaries on the closet shelf, underneath a moth-eaten purple sweater, because one can never be too careful.

“Yes, I read them,” says Lucy. “I’m not going to apologize. Anyone would have done it.”

When I first started keeping a diary, in the sixth grade, I was writing with the notion that it would be read one day. I wrote neat entries in a voice that wasn’t my own. I addressed the diary as if it were a person, beginning pages with “Guess what?” and ending them with “Goodnight!”

I had in my head the image of the person my diary was. I could see a construction of its personality, and intuit the responses it would write to me if it could. I imagined it offering advice, sympathy, and companionship.

In high school, I stamped out my frustration in inelegant passages, my sentences hanging off the lines of the paper. After writing, I was embarrassed, as if I’d blurted out a secret on stage to an audience. Writing in the diary should have felt private but the image of the book as a person returned to me. I wondered, illogically, if my diary found me boring, or frivolous, or whether she was disappointed in how her writer had turned out.

“Maybe I shouldn’t have read them,” says Lucy, “but I did. And I think you should take it as a compliment. I read them because I was interested.”

Then, when I ask her how much she read, she switches tactics, “I barely read them,” says Lucy. “I mean, your most recent pages are all about school, and complaining about other people. I got sort of bored.”

The rest of the school day, I pick fights with Lucy. In the classes we share, I ask mutual friends whose side they’re on. I ask them whether they would have gone through their friend’s things the way she went through mine, and they laugh embarrassedly. I can tell I’m sort of making a scene.

It’s springtime. I track mud home on the soles of my boots and feel an irritating sludge sliding around in my head. I have the urge to pull out some of this mud, some of my frustration, and put it on paper.

I correct that impulse. Whatever I write down might later be read. What a grim thought. For years, I was ashamed of my urge to write without polish, or without purpose. I’d regretted the pages I’d written in anger and excitement. Yet now that I needed it most, I felt incapable of writing that way.

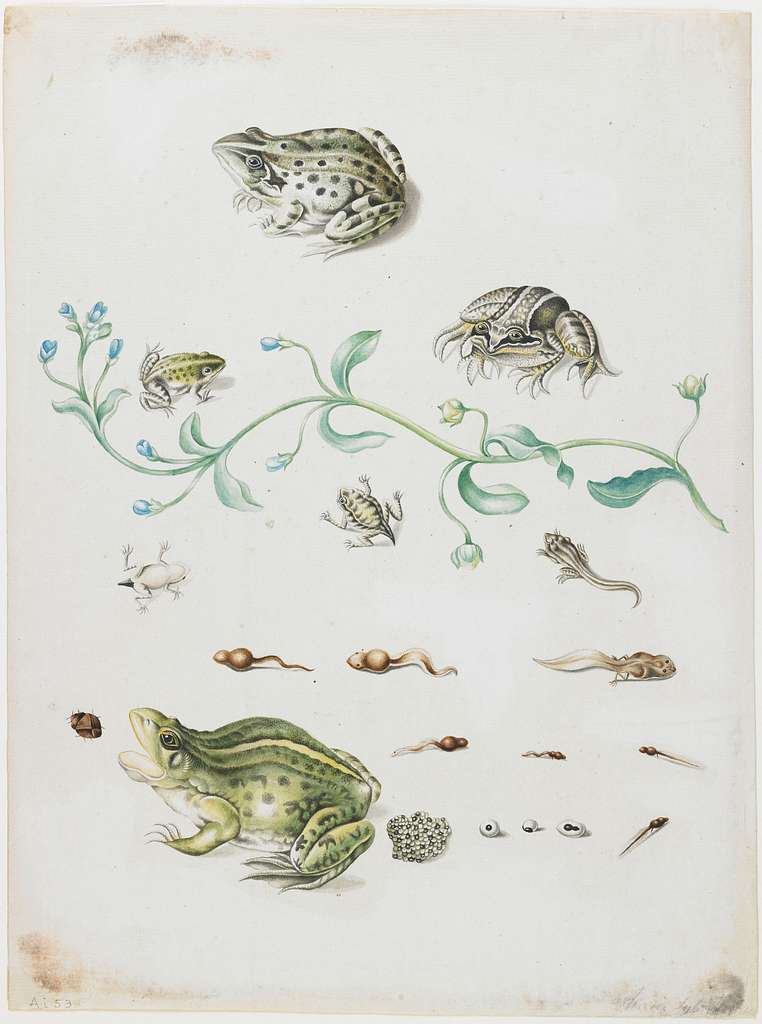

Over the next few weeks, I sit with indignation. I let it turn and spoil. I don’t write it out. Instead, I read back through my diary, where mistakes and cliches leer at me from the pages. There are five volumes, with kitschy covers emblazoned with illustrations of animals: the owl, the llama, the butterfly.

Written on the first page of my most recent book, I find a poem I wrote a few months before, which is addressed to my diary. It’s about my process of cataloguing my thoughts and experiences, so that I may one day use them in professional writing. It’s not perfect, but it isn’t a bad poem either. Slowly, I realize that this is something I wouldn’t mind having other people read.

I’m shy about this poem and the handful of others I pick out of the pages, like unripe fruit from a tree. Still, I submit them to a school poetry contest after some revision and win a spot to read my poetry at a Literary Festival.

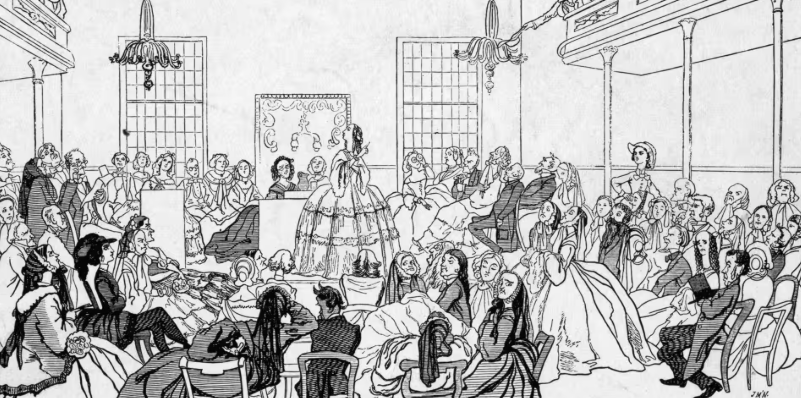

This festival will host famous writers this weekend, but we high school students are invited on Thursday night and brought into a small lecture hall at Montclair State University. There are nine of us, from three local schools, and the name of the event trumpets us as “The Voices of Tomorrow.”

I’m wearing a corduroy skirt, which keeps shifting around so that the buttons that dot down the front often sit at the side of my leg instead. My poetry is printed on a piece of white paper in 16-point font so that I can make out the words when I start to stutter, which I’m sure I’ll do.

Most of the audience, it seems, are parents and friends of three private school students, two girls and a boy. In my nervous state, these other kids appear to be seven feet tall, with pointed teeth and claws.

At the podium, as I read my poetry to the sparse crowd, I feel relieved. I begin to feel that all of my dissatisfaction with my writing skills is shriveling up and shrinking away in the light of what I’m doing now. It no longer matters that my writing is often awkward, convoluted, and disorganized. It doesn’t even matter that my private thoughts were spied upon. To share my writing with an audience is wonderful. My mind feels light and dry as if it’s been wrung out and refreshed.